|

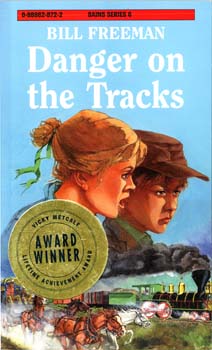

Danger on the Tracks

|

|---|

(Meg and Jamie are traveling to the railway construction camp by train.) Jamie watched the thick black smoke pouring out of the onion-shaped stack of the engine up ahead. He was not looking forward to the kitchen job. If only he could be an engineer of a locomotive. He imagined himself leaning out of the window with the wind in his hair and his hand on the throttle. He wanted to learn about how steam power drove engines, and the inner workings of complicated machinery. Perhaps if he showed Sam Bolt that he was eager to learn, the engineer might agree to explain things. Up ahead the locomotive whistle gave a long blast as they crossed a road. The train was going twenty miles an hour or more now. They seemed to be rushing through the countryside, past buildings and fields, at breakneck speed. Jamie stood up and began to make his way to the front of the car. “Where are you going?” Meg called after him. “Up to the engine.” “You can’t do that.” She got to her feet and began following him. “It’s against the rules.” But Jamie ignored her. At the forward end of the flatcar, the boy paused to look at the ground rushing past. The noise of the steel wheels, squealing and clacking as they hit the rail joints, was deafening. Cautiously he leaned forward, grabbed the ladder of the boxcar that was just ahead and then leapt onto it. In a moment he scrambled up to the top of the car and began making his way forward on the narrow cat-walk. Meg didn’t know what to do. She was sure there had to be rules against going up to the engine, but she couldn’t let her brother go alone. She stood at the front of the flatcar and gazed through the gaping space at the ground rushing past. The train rolled and pitched on the uneven track. She hitched up her dress with one hand and leaned forward until she could grab a rung of the ladder on the boxcar. Then with a leap she was onto the ladder and climbing up. When she peered over the top of the boxcar she could see Jamie a couple of cars ahead. He paused for a moment, then took a quick run and leapt for the next car. Meg’s heart almost stopped, but he landed on his feet and kept going. Meg pulled herself to the roof of the car and stood up. The train rolled like a ship at sea. The wind was rushing at her, tugging at her ankle-length dress as if trying to blow her off the car. Cautiously she made her way forward, keeping to the narrow cat-walk, bending into the wind that howled around her. When she got to the front of the car she stopped. Ahead of her was a five-foot chasm. The car rocked unsteadily, the wind billowed her dress like a sail, smoke from the engine caught in her throat, and the ground rushed by with dizzying speed. If she jumped and missed, she would fall between the cars and be crushed under the giant steel wheels of the train. Panic seized her, but she fought against it. Cautiously she backed up, hitched up her long dress with one hand, and concentrated on the open space between the two cars. She sprinted, a cry coming from her throat, then leapt, thinking only about the car ahead. The moment she landed she scrambled to her feet and kept going without looking back. Four more times she had to jump between the moving boxcars. Each time she knew that if she missed, it would mean certain death. But she pressed on and finally made it to the cab. “You shouldn’t have come forward!” she shouted at Jamie over the noise. “Sam doesn’t mind.” “It’s against the rules,” the engineer said, looking at them critically. “You just won’t listen, Jamie. Come on, we’ve got to go back.” She turned to the trainman standing at his controls. “I’m sorry, Sam.” “Well, as long as you’re here, I guess it’s all right.” “See …” Jamie smiled in triumph. “But if you’re in the cab, you’ve got to work for your keep. You can help Jay fill the firebox, boy. Hustle to it.” Jamie found it was back-breaking work. He had to climb into the tender and wrestle out the four-foot pieces of cord wood which Jay shoved into the ever-hungry fire. They were heavy pieces of maple and birch. It wasn’t long before the boy’s clothes were filthy, and he was tired. Sam blew blasts on his whistle. “Hyde Park Junction. This is where we branch off the main line and take the London, Huron and Bruce.” Meg leaned out of the cab window and watched while the switchman wrestled with the big steel arm that changed the track. When it was thrown, a hand signal was given, Sam opened the throttle, and the train switched off the main line and onto the new track heading north. Now they were passing open fields, concession roads and the occasional farm house. It was rolling country with stands of hardwood, turning a golden yellow and deep red, scattered in among pastures and fields of stubbled grain. Occasionally they went past fields with stacks of hay drying in the late afternoon sun. There was a warmth and prosperity about the land that made it glow. The train was rolling down the tack at little better than a walking pace. “She’s not ballasted yet,” Sam explained. “Ballasted?” asked Jamie. “They’ve got to pack gravel and cinders and rock all around the ties to hold them down. This track was only laid a few weeks ago. They haven’t had time to do it yet.” “If you have to go this slow you’d never beat a stagecoach in a race,” said Jamie. Sam sneered, “Bear him? There’s not a team of horses alive that can beat a train over a distance. The railway’s bringin’ a revolution to this country. It will let farmers market their goods and bring the products of the city out to the countryside. People will be able to read newspapers printed that day. The train is the great civilizer. It’s the end of the frontier and the beginning of a new life for these people. The stagecoach is a thing of the past.” Meg was thoughtful. “I guess that’s why Will Ryan hates the railroad so much. It would mean the end of his business.” “He’s just afraid of the future, that’s all.” Once they went through the tiny village of Ilderton, the engineer began opening up the throttle. They were steaming along at a good rate when Sam ordered Jamie to shake loose the smokestack. “Let’s see if you’ve got the makin’s of a railroader, boy.” As the wood burned in the firebox, it threw off red-hot cinders. A wire screen was fastened over the top of the smokestack to catch them, but after awhile so much accumulated that the smoke could hardly escape. Sam tied a red scarf around the boy’s nose and mouth, making him look like a bandit. Cautiously Jamie went out onto the running board of the engine and crept around the side of the locomotive. The wind was in his face. Trees, fields and farm buildings rushed past, and the train heaved on the uneven track. The boy had never felt such a sensation of speed in all his life. He bent down and got a long pole that was lashed to the running board. The train rolled and lurched, and he had to be careful not to touch the hot side of the big boiler. The wind surged around him, and the pole was heavy and awkward. It took all his effort, but he managed to manoeuvre it around until he could use it to hit the opening of the stack. With each knock of the pole, more cinders fell back into the firebox. Thick, black smoke came streaming out, catching in his nose and throat despite his mask. Cautiously Jamie put the pole back in place and made his way back to the cab. Sam was laughing. “Shakin’ down the cinders is the true test, boy.” Jamie beamed. The town of Brecon was down in a bit of a hollow. As they approached, Sam opened the throttle and blew a long warning blast. By the time they got to the bottom of the dip, it seemed as if they were flying. Sam hollered for more steam. Jay threw cord wood into the flaming inferno, slamming the door shut as quickly as possible. The engine roared and chugged its way up the grade until, with what seemed like a supreme effort, the train crested the hill. They were doing twenty-five, maybe thirty miles an hour. The big wheels hammered on the rail joints, the hitches rattled and the boiling water in the engines seethed violently. When Jay opened the fire door to feed the flames, a blast of red heat leapt out at them. As they went through the village of Clandeboye, Sam barely slackened his speed. At the crossing of the main street of town he blew a long, shrieking blast on his whistle. Meg saw a horse hitched to a carriage suddenly rear up in frights and paw the air with its front hooves. People on the street stopped to watch the speeding freight train. Children ran after them. Dogs barked wildly. San just laughed and opened his throttle further. “We’re gonna get there in record time,” he shouted happily. It was already beginning to get dark, but still Sam coaxed his locomotive faster and faster. The line ran a hundred yards or more to the west of the London-Goderich highway. From his position in the tender, handing cord wood to the fireman, Jamie could see wagons and carriages out on the road. The train steamed by them like they were standing still. The farms and trees hurtled past. Suddenly Sam was leaning out of his window. “There’s somethin’ on the line!!” Meg looked out the left side of the cab. A dark, massive object lay across the track a hundred yards ahead. In an instant Sam cut his throttle and frantically blew the down-brake signal on the whistle. “It’s a tree!” Again he blew the desperate signal to the brakeman. Already the big driving wheels were screaming on the tracks as Sam cut the power. But the tree still hurtled towards them at a terrible speed. “More brakes!” Sam screamed, and he gave a desperate blast on the whistle again. “We need all the brakes we’ve got, or we’ll never stop in time!” Each of the freight cars had its own brakes, and the brakeman, stationed in the caboose, would be up on top of the train turning them down. Jay, the fireman, leapt for the back of the tender and turned down its brake wheel. The armstrongs, as they called the brakes on the freight cars, were iron wheel-like affairs that stood a couple of feet over the top of the car. “Stop! Damn you, stop!!” The engineer screamed at his train. Again he frantically blew his brake signal. But they were coming too fast. The train rushed on. Meg watched the enormous object on the track grow larger and larger. “Hold on!!” The locomotive hit the tree with a bone-wrenching jar. Iron and steel crushed and crumpled. Glass shattered. Steam hissed. Wood thrown about in the tender, sounded like an avalanche. Somewhere a bell was clanging incessantly. The engine mounted up onto the tree, tipped slowly, teetered for a moment, and then fell onto its side. The two boxcars immediately behind twisted with the engine and fell with a shattering sound of splintering wood and metal. |

Find this book at Chapters Indigo

Download the teacher's guide

|

Download the teacher's guide

|